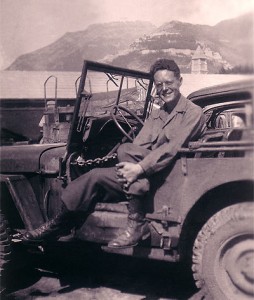

W. J. «Bill» STRAUSS (1912-1979)

by JULIAN, his son

The story of my father’s war experience is somewhat different from that of the thousands of young hometown boys who volunteered or were drafted into the armed forces to fight for freedom in the tremendous effort to destroy evil powers.

The story of my father’s war experience is somewhat different from that of the thousands of young hometown boys who volunteered or were drafted into the armed forces to fight for freedom in the tremendous effort to destroy evil powers.

William Strauss left Germany in 1933, when he had just turned 21 years old and when the Third Reich had just declared that Jews were no longer allowed to use German airfields, among other prohibitions.

As a young man, he was involved in the sport of flying and gliding and was frustrated by this turn of events.

He, therefore, decided to go to France, where he enrolled in an agricultural college.

He intended to emigrate, –leaving the family business in Frankfurt and leaving Europe with its ominous future,– and to become a farmer in a new land.

While in France, WJS met my mother, and together they immigrated to America in November 1935.

Strauss family: Julian, Eva and their mother

When shown Home Farm, the Guernsey-Agan farm in Amenia, by Mrs. Elizabeth Coons, a real estate broker of Smithfield, he immediately purchased it and began dairy farming. I was born shortly thereafter.

I can only imagine what it must have been like for my parents, as they watched history unfold in Europe with the spread of Nazism. When WWII broke out in Europe with the invasion of Poland, I was a small child and, with my mother, was visiting family in France. We hurriedly returned to the U.S., on the S.S. Normandie.

Germany’s blitzkrieg came in the spring of 1940. Holland, Belgium, and then France quickly fell before the onslaught; and darkness descended on all of Europe.

My mother’s family lived in Paris and in Normandy. Her brother (Danny Benedite) joined the French underground, after a year of working with an American, Varian Fry in Marseilles, helping Jewish and political refugees escape the tightening net of the Gestapo. Another uncle’s farmhouse in Normandy was taken and used by the occupying German army. My father’s brothers escaped from Germany, but there were other relatives who were murdered in concentration camps.

I don’t recall the conversations of the household, but I imagine they were intense. My father was eager to be involved in the war effort in some way. I do remember the announcement of the attack on PearlHarbor at the end of 1941, when I was five years old. My father tried to inlist but, having come from Germany, was rejected as an enemy alien.

Finally, in early 1943, he received a draft notice and left Home Earm and his family to serve. His first duty was as an Airplane Maintenance Technicia., stationed at Camp Butner, North Carolina, in the 78th Infantry, Lightning Division.

One day, while at Camp Butner, he was questioned by an officer in order to determine his proficiency in German and French, which of course was excellent. Following this he was asked if he would be interested in participating in a special operation. He immediately agreed. The following day, he was made a U.S. citizen and was transferred to Washington, D.C., to receive special training, on the grounds of the Congressional Country Club!

And, thus, William J. Strauss became a part of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

From that time on, throughout the remainder of the war, his family heard little of his whereabouts.

Much later, we learned that initially “Bill” and his buddies had been sent to North Africa for paratroop training.

Bill’s special operations group of fourteen men left one night in a four-motor British Lancaster. After several failed approaches, they jumped and landed about twelve miles from the prepared reception area in Southern France, in the middle of the Nazi army.

It was in a rocky, wooded area, and several men were injured, but they moved out and soon made contact with the local French Resistance group, the Maquis.

They had dropped with equipment, arms and explosives, and set about training and making plans to wreak havoc, by cutting Nazi communications, rail lines, roads and radioing back intelligence.

With their tiny band, they succeeded in blowing up bridges, ambushing truck convoys, derailing trains, destroying ammunition depots and liberating small cities in Southern France. It was a classic example of the newly developed effectiveness of the radio, the airplane, and the parachute used to equip and organize a willing partisan guerilla force to perform a coordinated plan of attack.

In all this, William Strauss, with his language ability and newly acquired skills as radio operator and demolitions technician, accomplished what he desired to do, that is, to strike a blow against Hitler for the sake of his new country.

For a proud new American citizen, one who had been raised as an “assimilated” German Jew, one who had been educated among German friends who were forced to fight for Hitler, this victorious war experience came at a great emotional price. For the rest of his life, Bill Strauss, husband, father and farmer, was troubled by the ravages of Hitler’s Third Reich, and by his own part in this terrible war.

Albeit, my father’s separation papers cryptically summarized his military experience in this manner:

Albeit, my father’s separation papers cryptically summarized his military experience in this manner:

“Intelligence N.C.O. — Worked with organization requiring paratroop training in execution of confidential assignment.”

As his son, my happiest memory of those WWII years is that of standing with my mother at the Amenia train station, looking for my dad among the train’s descending passengers and seeing him way down the line of cars.

As his son, my happiest memory of those WWII years is that of standing with my mother at the Amenia train station, looking for my dad among the train’s descending passengers and seeing him way down the line of cars.

I began to weep. Mr. Maxfield, the station master, asked why I was crying. “My daddy has come home,” I said.